Hello again, Reader.

I’ve been going over older posts, and thought that now would be as good a time as any to start building a glossary. It never hurts to be as clear as possible about what we mean when we use particular terms. The world of fabrics is full of them: the sheer number can overwhelm even the expert among us.

But not matter what your level of experience is, having a handy guide at your disposal to recall spellings, definitions, and examples can only help. Most of the definitions come from the Merriam-Webster or the trusty OED, although I’ve cut out some of the more superfluous bits, and focused on the really important, juicy stuff, so that you can find the information you want at a quick glance.

So here’s the beginning of an on-going glossary of terms that crop up frequently in this exciting, varied world. Let’s get stuck in!

A

Angora: downy coat produced by the Angora rabbit.

Angora

B

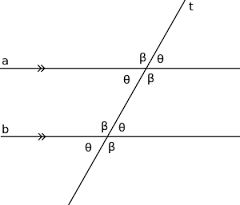

Batik: (n) a fabric printed by an Indonesian method of hand-printing textiles by coating with wax the parts not to be dyed; the method itself.

Batik

Bobbin: (n) a round object with flat ends and a tube in its center around which thread or yarn is wound.

Bobbinet: (n) a machine-made net of cotton, silk, or nylon usually with hexagonal mesh.

Boiled wool: (n) created by a mechanical process using water and agitation, shrinking knitted or woven wool or wool-blend fabrics, compressing and interlocking the fibers into a tighter felt-like mass.

Bouclé:(n) an uneven yarn of three plies one of which forms loops at intervals.

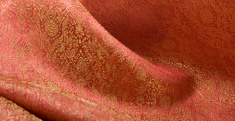

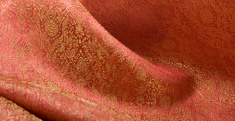

Brocade:(n) a cloth with a raised design in gold or silver thread.

Brocade

Bunting:(n) a lightweight loosely woven fabric used chiefly for flags and festive decorations.

Burlap:(n) a strong, rough fabric that is used mostly for making bags.

C

Calico:(n) a light, printed cotton cloth :a heavy, plain white cotton cloth

Calico

Cambric:(n) a light, thin, white linen or cotton cloth

Cashmere:(n) a fine wool from a kind of goat from India :a soft fabric made from cashmere wool.

Chambray:(n) a lightweight clothing fabric with colored warp and white filling yarns.

Charmeuse:(n) a fine semi-lustrous crepe in satin weave.

Chenille:(n) a wool, cotton, silk, or rayon yarn with protruding pile;also:a pile-face fabric with a filling of this yarn.

Chiffon:(n) a sheer fabric especially of silk.

Chiffon

Chintz:(n) a shiny cotton fabric with a flowery pattern printed on it.

Cloth: a flexible material consisting of a network of natural or artificial fibres.

Corduroy:(n) a durable usually cotton pile fabric with vertical ribs or wales.

Cotton:(n) a soft, white material that grows on the seeds of a tall plant and that is used to make cloth;also: the plants on which this material grows.

Cotton

Cotton gin:(n) a machine that separates the seeds, hulls, and foreign material from cotton.

Crêpe:(n) a thin often silk or cotton cloth that has many very small wrinkles all over its surface.

Crinoline:(n) an open-weave fabric of horsehair or cotton that is usually stiffened and used especially for interlinings and millinery.

Crochet:(v) a method of making cloth or clothing by using a needle with a hook at the end to form and weave loops in a thread.

D

Damask:(n) a thick usually shiny cloth that has patterns woven into it.

Denim:(n) a firm durable twilled usually cotton fabric woven with colored warp and white filling threads.

Denim

Double knit:(n) a knitted fabric (as wool) made with a double set of needles to produce a double thickness of fabric with each thickness joined by interlocking stitches: an article of clothing made of such fabric

Double weave: (n) a kind of woven textile in which two or more sets of warps and one or more sets of weft or filling yarns are interconnected to form a two-layered cloth, allowing complex patterns and surface textures to be created.

Duck:(n) (Dutch) also simply duck, sometimes duck cloth or duck canvas, a heavy, plain woven cotton fabric.

E

Embroidery:(n) the art or process of forming decorative designs with hand or machine needlework:a design or decoration formed by or as if by embroidery: an object decorated with embroidery.

Embroidery

Embroidery floss:(n) a loosely twisted, slightly glossy 6-strand thread, usually of cotton but also manufactured in silk, linen, and rayon, and the standard thread for cross-stitch.

F

Fabric: (n) any textile or cloth that is considered to be man-made.

Faille:(n) a somewhat shiny closely woven silk, rayon, or cotton fabric characterized by slight ribs in the weft.

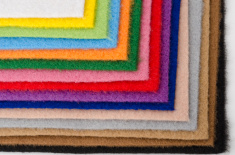

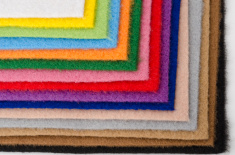

Felt: (n) a soft, heavy cloth made by pressing together fibers of wool, cotton, or other materials.

Felt

Fibre: (n) (Latin) a natural or synthetic substance that is significantly longer than it is wide.

Fishnet:(n) a coarse, open-mesh fabric.

Flannel:(n) a soft twilled wool or worsted fabric with a loose texture and a slightly napped surface: a napped cotton fabric of soft yarns simulating the texture of wool flannel: a cotton fabric usually napped on one side.

Fleece:(n) the coat of wool covering a wool-bearing animal (as a sheep): the wool obtained from a sheep at one shearing: any of various soft or woolly coverings: a soft bulky deep-piled knitted or woven fabric used chiefly for clothing.

G

Gabardine:(n) a firm hard-finish durable fabric (as of wool or rayon) twilled with diagonal ribs on the right side.

Gauze: (n) a thin often transparent fabric used chiefly for clothing or draperies: a loosely woven cotton surgical dressing.

Georgette:(n) a sheer crepe woven from hard-twisted yarns to produce a dull pebbly surface.

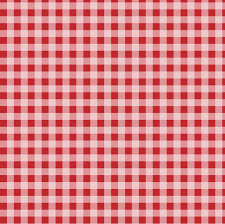

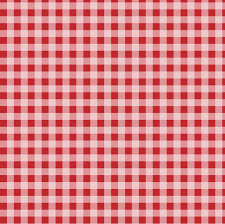

Gingham:(n) a clothing fabric usually of yarn-dyed cotton in plain weave.

Gingham

Grosgrain: (n) a strong close-woven corded fabric usually of silk or rayon and often with cotton filler.

H

Haircloth: (n) any of various stiff wiry fabrics especially of horsehair or camel hair used for upholstery or for stiffening in garments.

Heather: (adj) refers to interwoven yarns of mixed colors producing flecks of an alternate color. It is typically used to mix multiple shades of grey or grey with another color to produce a muted shade (e.g., heather green), but any two colors can be mixed, including bright colors.

Hemp: (n) a tall widely cultivated Asian herb (Cannabis sativaof the family Cannabaceae, the hemp family) that has a tough bast fiber used especially for cordage and that is often separated into a tall loosely branched species (C. sativa) and a low-growing densely branched species (C. indica): the fiber of hemp.

Herringbone:(n) a pattern made up of rows of parallel lines which in any two adjacent rows slope in opposite directions: a twilled fabric with a herringbone pattern; also :a suit made of this fabric

Herringbone

Holland cloth: (n) a plain woven or dull-finish linen used as furniture covering or a cotton fabric made more or less opaque by a glazed or unglazed finish (the Holland finish).

Houndstooth:(adj) a usually small broken-check textile pattern; also: a fabric woven in this pattern —called also houndstooth check, hound’s-tooth check.

I will be continually up-dating these posts with new terms, and, as the title of this post suggests, there will be two more ‘Glossary’ posts, for I-P, and Q-Z, so keep an eye peeled for those! Looking for a particular definition, term, or information that you don’t see? Leave your comments, questions, and requests below! I’m looking forward to hearing from you!

Until next time, Reader.

Yours,

Cotton Jenny

![20160306_130728[1]](https://cottonjennyfabrics.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/20160306_1307281.jpg?w=224&h=401) (any colour- I usually try to have two colours for petals and leaves, but that’s up

(any colour- I usually try to have two colours for petals and leaves, but that’s up![20160306_130914[1].jpg](https://cottonjennyfabrics.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/20160306_1309141.jpg?w=640)

![20160306_130955[1].jpg](https://cottonjennyfabrics.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/20160306_1309551.jpg?w=542&h=303)

![20160306_131045[1]](https://cottonjennyfabrics.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/20160306_1310451.jpg?w=608&h=340)

![20160306_131145[1]](https://cottonjennyfabrics.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/20160306_1311451.jpg?w=195&h=349)

![20160306_131423[1].jpg](https://cottonjennyfabrics.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/20160306_1314231.jpg?w=485&h=868)

![20160306_131537[1].jpg](https://cottonjennyfabrics.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/20160306_1315371.jpg?w=640)