Hello Reader.

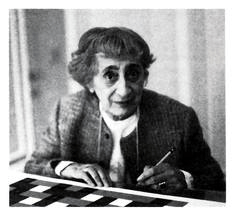

As some of you may know, if you’ve checked out my Pinterest boards, (Cotton Jenny) I really like children’s literature and story-telling. I also really like textiles and fabrics. These two passions collide in the work of an amazing lady called Faith Ringgold.

I’m pretty sure she is one of the coolest textile artists around. I first saw her work on the classic, and sadly no-more, children’s television programme Reading Rainbow. They had a great segment where someone would come and read a story to you, and the pages would turn like you were looking at a real book, and the camera would pan across the page as the narrative progressed.

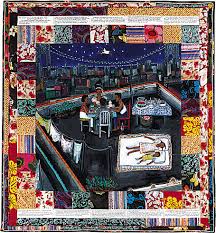

Well, one day, the book on offer was Ringgold’s brilliant Tar Beach . The book details the story of a young girl who imagines herself flying over her city at night as she lies on Tar Beach: the roof of her apartment building. The illustrations came from Ringgold’s quilt of the same name. I was transfixed.

Fast forward several years, and I was writing a paper about her for a second-year Women in Art class at university. I got to know some of her other works, besides Tar Beach. Let me share what I learned with you.

Ringgold was born in 1930 in Harlem, New York City. Her mother worked as a seamstress and fashion designer, so Ringgold grew up around fabric. She received her Bachelor’s degree from the City College of New York. For several years afterwards, she taught in the New York Public School system. She eventually returned to school, and earned her Master’s degree from City College in 1959.

Ringgold started out life as a painter. In the 1960s, she adopted a style of flattened, figural compositions, but her work was rejected by many critics because it bore little resemblance to popular styles and motifs from that time. In the 1970’s, she worked in sculpture, focusing on depictions of historical and contemporary women of colour. It wasn’t until the 1980’s that Ringgold began to work on fabric. She developed a practice of making painted story quilts, which seem to incorporate her education in painting with her familial background in fabrics. It’s these story quilts I want to focus on.

A quilt called Quilting Bee at Arles shows a group of figures standing around a finished quilt, which features a sunflower motif, while actual sunflowers grow behind them. A lone figures stands apart from the group. The quilting group is made up of black women of different ages. Their voices can be heard in the written narrative that circles the quilt. Ringgold writes out the words the speak on the border of the quilt. These words give us information about what is going on in this image. The women assert that through their quilting work, they are going to make the world run right again. These women are named: among them stand, left to right, Madam Walker, Sojourner Truth, Ida Wells, Fannie Lou Hammer, Harriet Tubman, Rosa Parks, Mary McLeod Bethune, and Ella Baker. They are joined by a character developed by Ringgold, Willia Marie Simone, who some have argued stands for Ringgold herself. The combination of the sunflowers and the title, which tells us that this is taking place at Arles, gives us clues about who the lone figure might be. He is Vincent van Gogh, well-known Dutch painter, whose still-lifes of sunflowers are among his most acclaimed works. I think this work is Ringgold’s clever and subtle way of suggesting that perhaps it is time for women of colour to be the focus of art and art production: white men have had plenty of time in the spotlight. It is also possible that she means to indicate that the work of women of colour has the power to make positive changes in the world.It also positions women of colour and textile artists as equal to more well-known male artists, like van Gogh. On it’s surface, it’s a bright and cheerful quilt about quilting. Look harder, though, and this quilt seems to demand that we pay more attention to artists of colour, and the stories they want to tell.

Another fascinating example is Ringgold’s Dancing at the Louvre. Ringgold travelled to Europe as part of her art training, and this quilt might be inspired by her experiences in Paris. This quilt shows us several figures engaged in a lively dance before three famous paintings in the Louvre’s collection: most notable among them is La Giaconde, or the Mona Lisa. (The other two works are also paintings by Leonardo da Vinci.) Here we meet Willia Marie Simone again: she is the dancing woman in the yellow and white dress. In this image, I think we can see Ringgold actively re-writing a historical narritive. Here, she combines traditions of African dance and American quilting with European art collections. Arguably, the performance by Simone, her children, and her friend, is as much a work of art as any of the three paintings on the wall.

The final work I want to look at with you, Reader, is her Tar Beach, the very same quilt I first saw years ago on Reading Rainbow. This quilt features a central image, surrounded by quilted squares of fabric and two horizontal bands of text, which tell the story of young Cassie, and her adventures in flying from Tar Beach over her city each night. Cassie is depicted twice: once on the mattress, star-gazing with her younger brother, and again in the sky, flying over the lights of a distant bridge. We can read this image more than one way. We might see this as a depiction of Cassie dreaming: we are seeing her as she sees herself: flying over her home. It might also be a kind of two-part narrative. The first part of the story shows us Cassie on Tar Beach. The second ‘act’ of the story has Cassie flying. A third reading might be that Cassie is in both places at once: her physical self is lying on Tar Beach with her family, but her spiritual self is free to fly among the stars. This reading aligns itself with some African traditions of dualism: that is, the soul and the body are made of different substances, and can act independently of one another.The presence of the bridge in the background also suggests that we might read this image as an expression of Cassie’s growth into womanhood. She is at once a child and a woman, earth-bound and heavenly, seeing the lights of the bridge before her like beads on a necklace that she wants to wear. Again, we see Ringgold combining different aspects of her art training and background to develop a visually fascinating, but also ambiguous, narrative.

I was lucky enough to meet Ringgold about two years ago. I was very nervous: I felt as though I was in a room with a giant. She was very kind to me. She had on the coolest pair of red leather cowboy boots I have ever seen. She is a great story-teller, and answered questions in a no-nonsense, straightforward way. Luckily for us, Ringgold writes her stories as well as quilting them. She has a remarkable body of written work, which includes memoirs as well as children’s literature. I recommend starting with Tar Beach.(Find it here) The illustrations and the words are soaring and wonderful. And who among us, Reader, has never dreamed of flying?

Yours

Cotton Jenny